A new preprint to the arXiv discusses Caltech’s decision to repudiate the Nobel laureate Robert Millikan. The preprint takes the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) to task for its decision. What follows is a digest of that 64-page preprint.

Nobel Laureate in physics

Robert A. Millikan (1868-1953) was the second American to win the Nobel Prize in physics. At the peak of his influence, no scientist save Einstein was more admired by the American public.

Millikan’s greatest scientific achievement was the isolation the electron and the measurement of its charge. Millikan was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1923 for the famous oil-drop experiment, which measured the electron charge. These measurements also led to reliable estimates of Avogadro’s number.

His second greatest scientific achievement was the experimental verification of Albert Einstein’s photoelectric equation, which was also recognized by the Nobel Prize. Einstein’s and Millikan’s Nobel Prizes are closely linked: Einstein’s for the theoretical derivation the photoelectric equation and Millikan’s for the experimental verification. (Contrary to what some might expect, Einstein’s Nobel Prize was not for the theory of relativity.) As a bonus, Millikan obtained what was then the best experimental value of Planck’s constant.

The photoelectric effect gave one of the first strong indications of wave-particle duality. Even today, wave-particle duality poses puzzling philosophical questions. Einstein hypothesized the existence of what is now called a photon – a hypothesis that flew in the face of the settled science of wave optics. This unsettling concept of light motivated Millikan in his experiments, and he eventually confirmed Einstein’s equation. The photon and the electron were the first in the timeline of many elementary particles. Millikan’s student Anderson later won a Nobel prize for the discovery of the positron.

Head of Caltech

Millikan, the head of Caltech during its first 24 years, oversaw its rapid growth into one of the leading scientific institutions of the world. Millikan was appointed the chief executive of Caltech in 1921, the year after an unexceptional manual training school was renamed the California Institute of Technology. He was offered the title of president but instead chose an organizational structure that made him the chairman of an eight-member executive council.

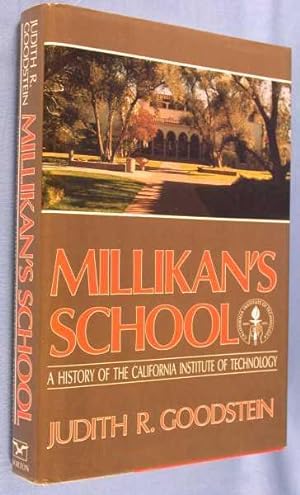

When Millikan first arrived at Caltech, “the faculty and graduate students were still a small enough group so that at the first faculty dinner we could all sit around a single long table in the basement of the Crown Hotel.” Through Millikan’s vigorous leadership, Caltech swiftly grew. “Millikan was everywhere planning, deciding, admonishing.” Linus Pauling wrote, “Millikan became a great public figure, who in the minds of the people of the country represented the California Institute of Technology….” The book jacket to Goodstein’s history of Caltech states, “To the public in the early days, Caltech soon became known as ‘Millikan’s school’ for Millikan, who functioned as the school’s president, brought to Pasadena the best and the brightest from all over the world….” According to Goodstein, “by 1930, Caltech was ranked as the leading producer of important physics papers in the country.”

In education, Millikan and Gale’s “First Course in Physics” is perhaps the best selling English-language physics textbook of all time. Including all editions and title variations, Millikan and Gale sold over 1.6 million copies between 1906 and 1952. It is particularly remarkable that these numbers were achieved in the first half of the twentieth century, when the physics textbook market was much smaller than it is now. In the international textbook market, “The Feynman Lectures on Physics” (another Caltech icon) holds the record with more than 1.5 million English-language copies and many more in foreign translation.

Demands for social justice

In response to demands for social justice following the murder of George Floyd, Caltech launched an investigation into Millikan. Caltech reached a decision to strip Millikan of honors (such as the library named after him), following accusations from various sources that he was a sexist, racist, xenophobic, antisemitic, pro-eugenic Nazi sympathizer. In short, Millikan’s School threw the book at Millikan.

Japanese internment camps

An article in Nature about Caltech’s decision accused Millikan of collaborating with US military to deprive Japanese Americans of their rights during their forced relocation to internment camps during the Second World War. The Caltech report on Millikan draws a similar conclusion. An examination of original historical sources shows that this accusation is false. On the contrary, Millikan actively campaigned during the war to promote the rights of Japanese Americans. The preprint traces the stages of misrepresentation that led to current false beliefs about Millikan.

Here is some relevant context.

- After the end of World War II, the US Army, Navy, and Air Force organized large expeditions to Japan to evaluate Japan’s scientific capabilities. The physicist Waterman (remembered today for the Waterman Award) asked Millikan for names of Japanese scientists and engineers who had studied at Caltech to assist in the scientific expeditions to Japan. The Nature article and the Caltech report completely misunderstood the historical context of the scientific expeditions, conflating the scientific expeditions to Japan after the war with Japanese internment in the United States during the war. On the basis of this glaring misunderstanding, Caltech unjustly criticized Millikan for his treatment of Japanese-Americans.

- In fact, during the war, Millikan was an officer in the Fair Play Committee, an organization that was formed in Berkeley to defend the rights of Japanese Americans. The day after the proclamation from FDR that ended internment, the chairman of the Japanese community council at one of the internment camps wrote a personal thank-you note to Millikan, saying “We realize that you played no small part in realizing this very important move” (of lifting the restriction on Japanese). Millikan received the Kansha award, which recognizes “individuals who aided Japanese Americans during World War II.”

Eugenics

The preprint also treats Caltech’s central accusation against Millikan: he lent his name to “a morally reprehensible eugenics movement” that had been scientifically discredited in his time. The preprint considers the statements in the Caltech report purporting to show that eugenics movement had been denounced by the scientific community by 1938. In a dramatic reversal of Caltech’s claims, all three of Caltech’s scientific witnesses against eugenics – including two Nobel laureates – were actually pro-eugenic to varying degrees. Based on available evidence, Millikan held milder views on eugenics than Caltech’s witnesses against him. The preprint concludes that Millikan’s beliefs fell within acceptable scientific norms of his day.

The history of eugenics has become a significant academic discipline, and a few paragraphs cannot do justice to the topic. The word eugenics evokes many connotations; a starting point is the Oxford English Dictionary definition of eugenics: “the study of how to arrange reproduction within a human population to increase the occurrence of heritable characteristics regarded as desirable.” From this starting point, the definition diverges in many directions. In California, eugenic practice took the form of a large sterilization program. The state government ran several hospitals for the care of those with mental illness or intellectual disabilities. During the years 1909-1979, over twenty thousand patients at those hospitals were sterilized. The “operations were ordered at the discretion of the hospital superintendents,” as authorized by California law. About three-quarters of sterilizations in California in 1936 were performed by request or consent of the patient or guardian (but the legal and ethical standards of informed consent fall short of what they are today).

The preprint devotes several pages to Millikan’s relationship with the eugenics movement.

- Where did Millikan fit into the eugenics movement? Millikan was a bit player. His name does not appear in the definitive histories of eugenics, and biographies of Millikan do not mention eugenics. Caltech emeritus professor Daniel J. Kevles, who is a leading authority on both Millikan and eugenics, did not mention Millikan in his history of eugenics. Overwhelmingly, Millikan’s most significant contribution to the biological sciences was his part in establishing Caltech’s division of biology. Caltech was his legacy.

- As reported in the Los Angeles Times, Millikan was strongly opposed to eugenics in 1925. He denounced the race degeneration theories of Lothrop Stoddard. Millikan maintained, “We can’t control the germ plasm but we can control education” and consequently, education was the “supreme problem” and a “great duty.”

- The only other sentence in Millikan’s own words about eugenics appeared in 1939 in an article in which he made forecasts about how science might change “life in America fifty or a hundred years hence.” He wrote, “I have no doubt that in the field of public health the control of disease, the cessation of the continuous reproduction of the unfit, etc., big advances will be made, but here I am not a competent witness, and I find on the whole those who are the most competent and informed the most conservative.” There is no mention of specific methods such as sterilization. There is no suggestion of the use of coercion. He speaks in the future tense, “advances will be made” in the coming fifty or hundred years. He is cautious. He humbly professes his lack of expertise.

- That is all that we have in the form of direct statements from Millikan on eugenics. The 1925 and 1939 statements from Millikan had not yet surfaced when Caltech issued its report. These direct statements from Millikan supersede the indirect case that was made in the Caltech report.

- Millikan joined the board of a Pasadena-based pro-sterilization organization called the Human Betterment Foundation in 1938. His reason for joining is not known. Millikan did not attend board meetings. His non-participation in the organization is documented in the form of signed proxy-vote slips that are in the Caltech archives for those years that the board met. There is no evidence that he read or endorsed the pamphlets issued by the foundation. Board members were free to disagree with the pamphlets, and sometimes they did. When the foundation closed down in 1942, its assets were donated to Caltech. It was Millikan who redirected the funds away from sterilization research.

- The section about eugenics in the Caltech report contains major historical falsehoods. The report used fabricated quotations from scientists of that era to make it appear that eugenics had been abandoned by the scientific community by the 1930s. To give one example, the report claims that in 1931 the Nobel laureate H. J. Muller denounced eugenics as an “unrealistic, ineffective, and anachronistic pseudoscience.” He made no such denunciation. In fact, Muller’s message was quite different: he said, it “is over course unquestionable” “that genetic imbeciles should be sterilized.” His 1936 book “Out of the Night” is a classic in eugenic writing. Muller continued to make a public case for eugenics until 1967, shortly before his death. In brief, Caltech got its history very wrong.

To be clear, nobody proposes a return to the California sterilization practices of the 1930s. According to science historian Alex Wellerstein, sterilization rates in California declined sharply in the early 1950s. The practice died not with a bang but a whimper. “No one took credit for killing the practice, and no one at the time appears to have noticed that it had ended.” “The horror we attach to sterilizations today, and to eugenics in general, did not become widespread until the 1970s, with the rise of interest in patient autonomy, women’s rights,” among other reasons (Wellerstein). During earlier decades, the largest institutional force in moral opposition to eugenics had been the Roman Catholic Church. The moral outrage at Caltech grew out of the Black Lives Matter movement and was directed toward the cause of “dismantling Caltech’s legacy of white supremacy.” The landscape has changed in other irreversible ways: birth control and genetic engineering have advanced far beyond the capabilities of the sterilization era.

Postscript on Diversity at Caltech

The preprint was written with a focus on Millikan. However, the larger message of the Caltech report is diversity. The word diversity and its inflections appear 78 times in the 77 page Caltech report. The word appears as many as nine times per page. The report, which is hosted by the Caltech diversity website, makes repeated reminders that Caltech has an “ongoing effort to forge a diverse and inclusive community.”

The Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Daniel Golden has written on admission practices at elite American universities. Caltech was unique among the most elite. Not long ago, Caltech boasted that on matters of admission, it made “no concessions to wealth, and it won’t sacrifice merit for diversity’s sake” (Golden, p278). David Baltimore, who was the president of Caltech, assured Golden that “Caltech would never compromise its standards. ‘People should be judged not by their parentage and wealth but by their skills and ability,… Any school that I’m associated with, I want to be a meritocracy'” (Golden,p284).

Never say never. The era of uncompromising standards at Caltech has come to an end. The Los Angeles Times reported on August 31, 2023 that Caltech is making historic changes to its admission standards. “In a groundbreaking step, the campus announced Thursday that it will drop admission requirements for calculus, physics, and chemistry courses for students who don’t have access to them and offer alternative paths….” “Data … showed a significant racial gap in access to those classes.” Caltech’s executive director of undergraduate admissions explained the new policy in these terms “‘I think that we’re really in a time where institutions have to decide if everything that they’ve been saying about diversity and inclusion is true,’ she said, noting that the challenge is especially acute now that the U.S. Supreme Court has banned affirmative action. ‘Is this something fundamental about who we are as an institution … or is this something that was just really nice window dressing.'” (LA Times, 2023).

The action against Millikan has been one campaign within a much larger political movement against standards of merit. Millikan himself had this to say about those who engage in mean-spirited attacks against America’s finest: “To attempt to spread poison over the United States with respect to the characters and motives of the finest, ablest and most public spirited men whom American has recently produced is resorting to a method which, it seems to me, all men of honesty and refinement can only abhor and detest.”

To be sure, Caltech has stirred up a hornets’ nest.

Your characterization of Caltech’s change in their admission policies appears misleading after reading the LA Times article. It seems like they are just allowing students whose schools do not offer calculus to study it online instead. They still need to score “90% or higher on a certification test” to qualify.

To me, this seems reasonable and an expansion of a merit-based conception of admissions. Before, a smart student who attended a school that, like 35% of American high schools, didn’t have calculus was being excluded out of no fault of their own. It’s arguably more impressive to self-study calculus and do well on a standardized test (provided it is difficult enough) than to take a normal class.

In contrast, Caltech’s choice to drop the ACT/SAT requirement is less defensible.